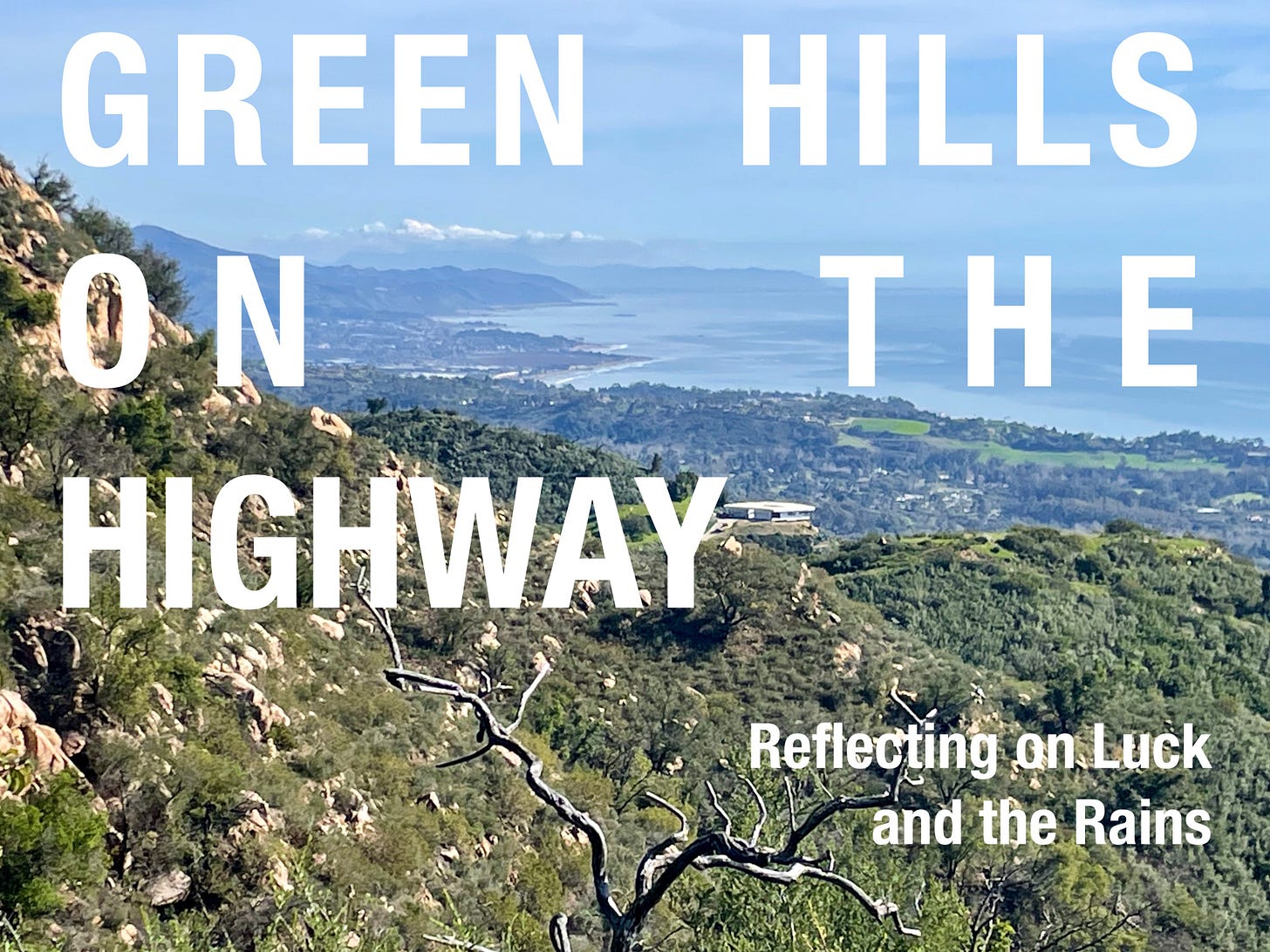

As I drove down to Santa Barbara, the last of the California deluge subsiding but still strong, I was in awe of the green hills. I thought it appeared as though I had driven through a TV screen almost like the movie Pleasantville. I meandered along Highway 101 which appeared identical to the background of every Dell computer from the early 2000s, submerged in blue skies, pure white clouds as the rains parted behind green hills so bright I might as well have been on acid. This is why people moved to California, I thought. This is that dream, now ever more left up to chance.

When I was living in Eugene, many of us loved to use the word synchronicity. The world, we thought when it felt to be working with us, was full of synchronicity, or good fortune. Fortuity wasn’t something that happened for good or bad, it was fundamentally good. We would hear a song that met our pain or joy and think how perfect that moment was, or we’d find ourselves getting coffee to do homework and run into someone we hadn’t seen in years, almost as though the world was conspiring for us to reunite. An astrologer my friend Noah loved, and whose horoscopes I still read now and again when I’m feeling lost or missing my friend, wrote a book called Pronoia which claimed that if you can believe that the world is capable of conspiring against you, you can believe it could conspire for you as well. I think he would have loved meeting our dreamy little mushroom crew.

It felt, for that whole trip down to Santa Barbara, as though the world was conspiring for me. On a whim I got to see two old friends I met in Eugene and whom I hadn’t seen in years, and was glad to see how little we had changed, how much the world had shifted us but how our essential selves, whatever that is, seemed so unchanged. Then I arrived in Santa Barbara, the rains easing, and my good friend Sandy, who I had gone down to visit, came home. The following morning I found a small local surf break completely empty save one person way out beside the edge of the cliffs, catching fewer waves than I was. Then I did some work in a small coffee shop, “Santeria” blasting as I walked into the cafe, something that seemed perfectly stereotypical of Santa Barbara. After that I got to see the studio where Sandy worked. I interviewed him about it, and now can finally understand clearly what amazing work he is doing—something that had evaded me for the past three years. My final day there, we went on a hike on a hill in the Montecito Hills, then we met Sandy’s friend, a billionaire whose house was the most beautiful and wildest museum of contemporary and modern art I’d ever seen (my car was parked beside a fucking Jeff Koons). After this we drove to Rincon to surf as the sun set. I caught one of the most beautiful waves of my life, after which a local said that he saw me catch a couple nice ones.

All of this was beautiful, serendipitous, synchronistic. We were able to do everything we wished we could. And yet, there was something in me that wasn’t present, or was conflicted by it all. Sure, this was magical (honestly I think Santa Barbara is the most ragingly beautiful place I have ever seen in my life), but why I was there, why my friend was there was clear and obvious. My friend was here, attempting to build something that might help make building as a whole more sustainable, and easier, something more necessary as the population expands into a growingly unwelcoming planet (a place created by rampant disregard). And I was there to surf, to write about my friend’s work that was funded partially by a billionaire, and to pretend all the problems of my daily life didn’t exist. We were there, in the midst of some of the strongest rainstorms in decades, attempting to share or create things that may help us survive in a growingly chaotic environment—an environment where we sometimes all we can do is pray for synchronicity.

On the way back up, no rain in sight, I talked with my brother. It was his birthday and, just having missed the rains, he was making a long ride from Santa Cruz to Pescadero on his bike. Lucky enough, he told me, it’s almost always sunny on his birthday. He said that someone recently told him that the best part about winter in California is that, once the rains have stopped, it’s immediately spring. It’s true. Sure, the rains hadn’t been this strong in years, and might not be again for a while, but from Santa Barbara up to Santa Cruz, we are lucky to see these places, often pictured gold from dry rocks and grasses, be made green. We are lucky to see it this way, far flung from the greater damages it brought

.