I parked out at the entrance of the Pacific Dunes Resort, just beside long croplands to the north and highway One. I walked past the mobile homes—most new, some residents but mostly a fair amount of over-landers, a slow moving caravan of travelers, wandering the United States by either circumstance or retirement.

It wasn’t early but most people were still inside and house finches kept flitting from bird feeder to bird feeder to some brush on the outskirts of the property in the bright yet quiet morning. Slowly I made it to the far end of the property and an opening in a wooden fence that led out to the rolling dunes—the thing I found on the map which I had come out there to see.

Approaching the fence a woman walked her dog to its edge, consenting to the “No Dogs Allowed” sign as her puppy whimpered while watching two dogs romping in the bright sand on the other side.

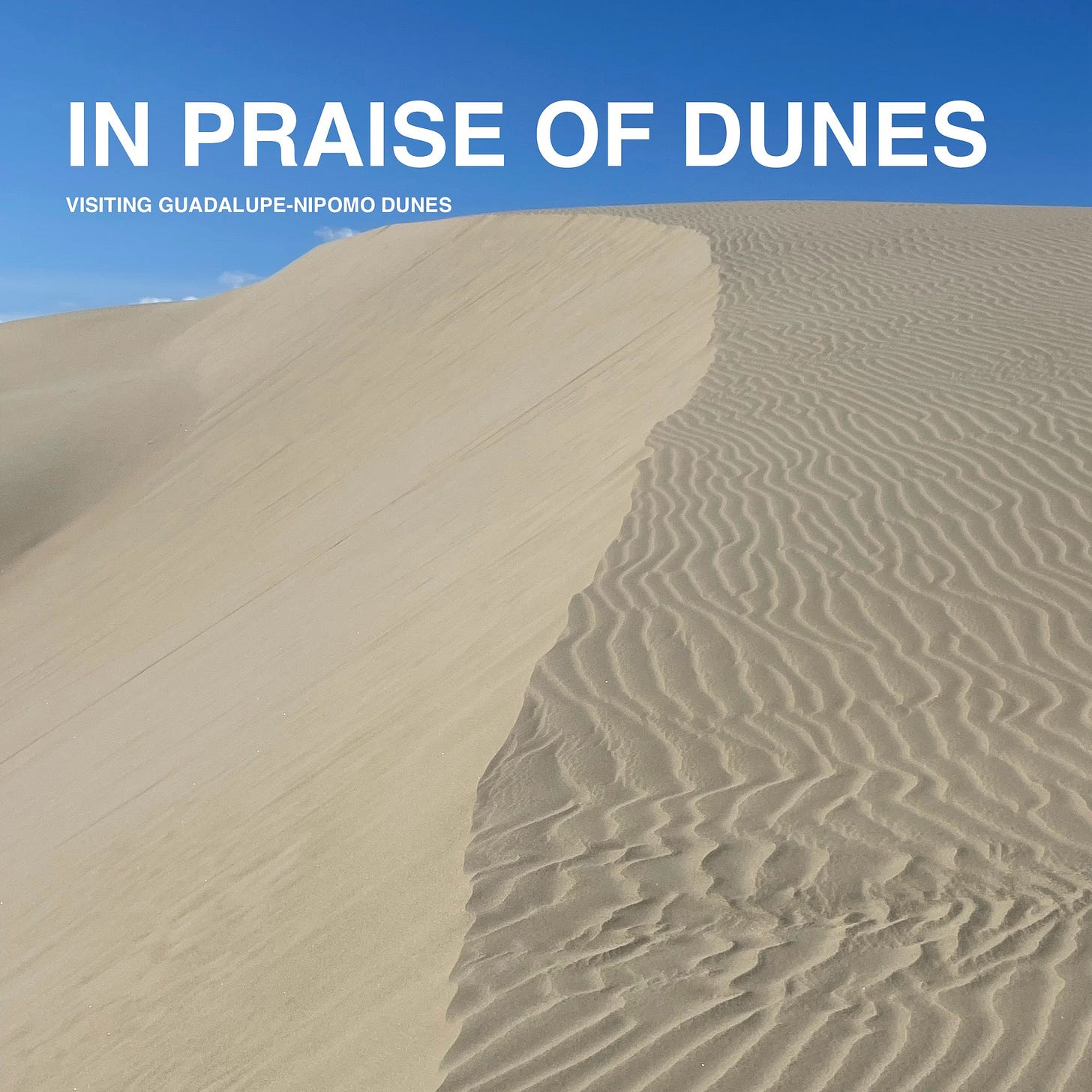

Entering deeper into the dunes, silence seemed to overtake me, like walking into the first heavy snow of a winter season, the world muffled by all this soft sand. Eventually passing over one dune, I couldn’t see the fence or the RV park anymore. I suddenly felt so far away, somewhat far-flung and even a bit lost. Looking at my footsteps behind me I saw that what I thought would be a straight line was in fact a meandering of curves around the edge of the taller dunes. Or maybe the lines were straight. Maybe it was only the shape of the hills of sand themselves that made it seem this way. It was hard to tell which it was. I was thankful it wasn’t windy and the sun was out. Without my steps and the sunlight I felt as though I could easily get lost, even at just a half mile into the dunes.

The sun, bright blue sky, silence, the soft hint of the beach half a mile from me, I felt stranded. It was a pleasant kind of stranded.

It’s truly hard to convey any kind of unique beauty into writing, and in a landscape such as this, like any open and surreal expanse, sometimes few can do it justice. Trying to communicate what that marvelous oddity appears before you just sometimes can’t be well described. Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes, where I was, are such a place. Ansel Adams photographed this place, along with Edward Weston, who took his famous nudes here. The 1956 film The Ten Commandments was shot there, the set famously buried where it was built, remnants still being rediscovered. The dunes were even home to a community in the early 20th century called the Dunites who used the place as a refuge from typical American ways of living. This place, I’m attempting to tell you, like so much of the central coast, is truly distinct, singular, and surreal in the quietude of it’s calm beauty.

Before the coast of California was colonized by Europeans, dunes maybe not as large but similarly majestic lined the coast of California. But, due to the introduction of ice plants and European beach grass to prevent the sand falling onto coastal roads and highways, the complex web of shifting sand that was the coastal dune ecosystem of western North America was almost entirely lost. The invasive plants, which are now almost synonymous with the California coast, along with coastal development, has now almost entirely eroded a once vital piece of California ecology, with snowy plovers, whose populations are always compromised by our presence, are the poster child of this once vast ecosystem.

There are efforts to preserve this ecosystem where they still exist from Guadalupe to the Lanphere and Ma-le'l Dunes just north of Eureka, and even expand them as a means to reduce the damages of sea level rise on coastal communities.

These dunes are simply magical, nothing you could ever expect to find in North America, but here they are, here they have been—a quiet unfathomable beauty that, much like the central coast itself, is a thankfully underrated marvel.